At any given time, there are over 11 million fake business listings on Google Maps. Over the last several years, the garage door industry has been plagued by this issue. Fake companies create listings on Google Maps, and attempt to disguise themselves as a local company in hopes to receive business from customers searching for the legitimate local companies within their area. Recently, Door & Access Systems Magazine published an enlightening article about a story that the Wall Street Journal published on the fake Google listings, and how it pertains to the garage door industry. The following article was published in the Fall 2019 issue of Door & Access Systems Magazine.

Wall Street Journal Exposes Millions of Fake Google Maps Listings

© 2019 Door & Access Systems

Publish Date: Fall 2019

Author: Tom Wadsworth

Pages 36-42

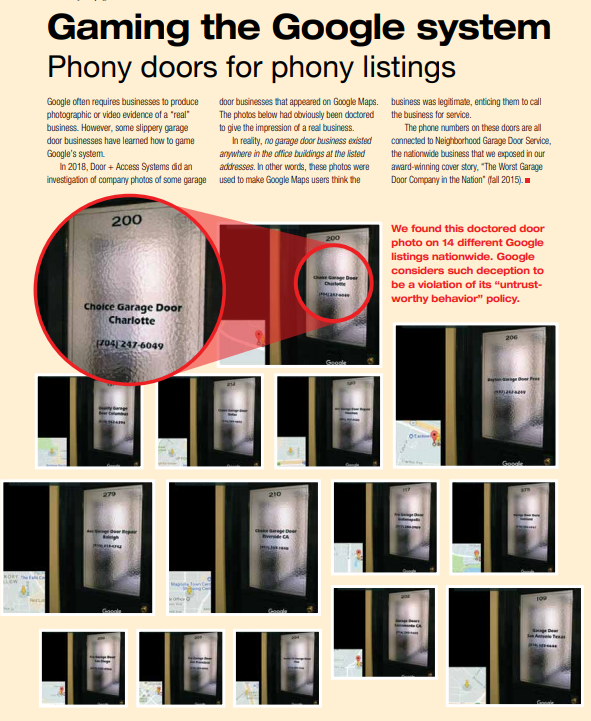

The garage door industry has taken another hit in the news media, thanks to the garage door repair scammers. But this hit might result in some positive change for our industry. On June 20, 2019, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), one of the top three newspapers in the United States by circulation, published this story online: “Millions of business listings on Google Maps are fake – and Google profits.” The same story, by Rob Copeland and Katherine Bindley, was published in its print editions with this title: “Google maps filled with false listings.” The article opens with the unfortunate experience of 67-yearold Nancy Carter of Falls Church, Va. After finding her garage door to be “stuck,” she used Google Maps to find and call a local garage door repair company. As the WSJ reported, she later learned that the repair company had “hijacked the name of a legitimate business on Google Maps.” The tech “fixed” her problem for $728, which was nearly twice the cost of previous repairs. Plus, the repair was “so shoddy it had to be redone.”

It’s all about Google Maps

But this story is not about the problems of garage door repair scammers. It’s about the problems of Google Maps and how they affect the garage door industry. “Google Maps … is overrun with millions of false business addresses and fake names,” said the Journal’s report. The garage door industry has known about this problem for years. So how did the WSJ find out about it? WSJ reporter Rob Copeland shared the background to his story in a July 3 podcast. He said he discovered the problem when he went to Mountain View, Calif., to visit Google’s headquarters. Before heading to Google, he did a Google Maps search for personal-injury attorneys and found 12 in Mountain View. Since he had rented a car, he took the time to actually drive to all 12 offices. He was stunned to find that only one of these offices was real. Many of the fakes were located in strip malls, office buildings, or construction sites. (The fake listings were used to solicit phone calls.) After he arrived at Google’s offices and reported his experience, Google apparently fixed the problem quickly. As he reported in his story, “the fakes vanished.” Lesson #1: Google can do something about this problem. But it helps when the Wall Street Journal

reports the problem to Google.

11 million fakes/day

“Hundreds of thousands of false listings sprout on Google Maps each month,” Copeland reported, citing expert sources. “Google Maps carries roughly 11 million falsely listed businesses on any given day.” How does this happen? WSJ reporter Katherine Bindley, co-author of the story, found some answers. She located a company in Hanover, Pa., that “can place as many as 3,800 fake Google Maps listings a day.” As Bindley noted in the July 3 podcast, she visited that company and learned that it has another staff of 25 in the Philippines. That’s where they generate the fake listings, charging $99 for one phony listing and up to $8,599 for a 100-pack. She reported that Hanover company to Google, who replied that they were investigating its operation. Amazingly, shortly thereafter, tens of thousands of the listings disappeared. Lesson #2: Google can do something about this problem. But it helps when the Wall Street Journal reports the problem to Google. (Yes, this is the same as Lesson #1.)

Google responds

On June 20, Google posted an article on its blogsite, directly responding to the thrust of the WSJ article. The post, titled “How we fight fake business profiles on Google Maps,” was written by Ethan Russell, the product director for Google Maps. Russell attempted to put the problem in perspective by noting the massive size of Google. He said, “Every month we connect people

to businesses more than nine billion times,” adding that Google gets millions of contributions each day, such as new business profiles, reviews, and star ratings. At the same time, Google is acutely aware of “business scammers (who) … use a wide range of deceptive techniques to try to game our system,” he said. “As we shut them down, they change their techniques, and the cycle continues.”

Fighting the problem

“We take these issues very seriously,” he said. Google is fighting the problem by using ever-evolving manual and automated systems. Russell wouldn’t share details about those efforts, saying that doing so might actually help scammers. On the positive side, Russell noted Google’s progress on this matter in the last year alone. He said that Google took down more than 3 million fake business profiles, noting that “more than 90% of those business profiles were removed before a user could even see the profile.” He also said that Google partially relies on users to report fake business profiles. More than 250,000 of the deleted fake business profiles were reported by users, he said. Google also disabled more than 150,000 user accounts that were found to be abusive. Russell said that this represented a 50% increase from 2017. It wasn’t clear whether the increase was due to improved monitoring by Google, increased scammer activity, or perhaps both.

Lesson #3

It was also noteworthy how quickly Google responded to the WSJ article. Russell’s response

was posted on June 20, on the same day the Journal’s article appeared in print. Lesson #3: Google can do something about this problem. But it helps when the Wall Street Journal reports the problem to Google. The good news is: Google is intensely aware of the problem, and they openly solicit your help in identifying these false listings.